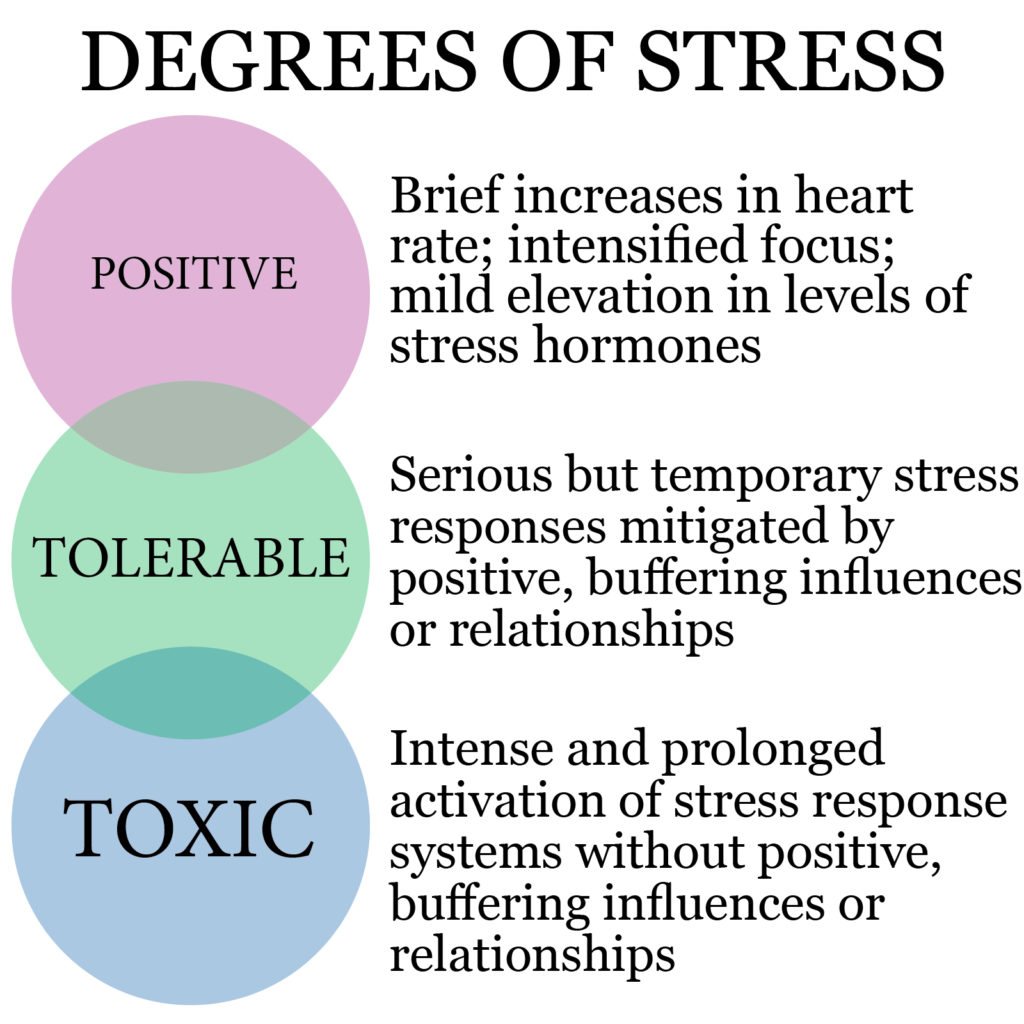

Between 40 and 50 percent of US marriages end in divorce. Divorce may seem commonplace, even mundane, these days but its prevalence is exactly what makes it such a threat to the healthy mental and physical development of children. While divorce may have become more socially acceptable in recent decades (or even ‘normalized’) the experience for children is almost universally difficult. There is no doubt that the conflict and chronic stress involved in divorce is one of the leading causes of trauma in young children and a very significant ACE (Adverse Childhood Experience).

Even when both parents agree that it’s the best decision, divorce is a confusing, difficult process for adults, let alone children. Divorce introduces new stressors into a child’s life. Whether the separation occurs when they’re three or 13, children worry about what’s happening to their family. Often, children experience feelings of fear, uncertainty, anger, and disappointment. To a child, a divorce can feel like a violation of trust or a broken promise. Most children rely on their homes to be a place of security and safety. Breaking up that home shakes their world to its core. Little brains that are still forming cannot process information in the same way a more reasoning adult can. Children tend to internalize feelings of guilt or self-blame over their parents’ divorce that can affect them for the rest of their lives.

True, there are millions of successful adults who grew up as children of divorce. While ‘pro-marriage’ groups say all divorce has negative impact on children, other studies do seem to indicate that it is preferable for unhappy parents to separate and care individually for their children than for children to be raised in two-parent homes filled with resentment or even rage. A recent British study shows that 82% of children (aged 14 to 22) whose parents divorced preferred their parents to separate agreeably than to ‘stay for the kids’. Divorce becomes an even more urgent decision when domestic abuse or violence against one or both partners (or the children themselves) is occurring. But there are as many adult children of divorce who are still trying to deal with the emotions and experiences their parents divorce caused them. Some studies indicate that the death of a parent (one of the most significant ACE indicators) may be easier for some children to understand and manage than divorce. In a child’s mind, it is easier to think that a parent died rather than that they left by choice.

Why is divorce such a powerful ACE?

• It introduces intense feelings of uncertainty, often for the first time if it happens very early in a child’s life

• It can cause an environment of chronic stress from anger, bitterness, and fighting

• It may cause economic strain on one of the divorcing parents

• It may separate the child not only from one parent but that parent’s family members who may have been a loving and stable influence

• It may expose a child to a parent’s new partners, which can increase risk of physical or sexual abuse

Of course, resilience levels among children are different. Some children cope and adapt better to divorce than others. Even among siblings experiencing the same divorce environment, the reactions may vary dramatically.

What Are the Warning Signs?

Here are just some of the indicators that your child may be having difficulties coping with your divorce:

• Poor performance or declining grades in school due to inability to focus

• Behavioral problems like attention seeking, “acting out”

• Mood swings or prolonged sadness/depression

• Apathy or loss of interest in places or activities they once enjoyed

• Less interest in spending time with friends

• Unwillingness to cooperate with everyday activities/defiance

• Low self-esteem and withdrawal

• Regressing to younger behaviors in an attempt to return to babyhood, clinginess

• New or increased irrational fears

If you’re dealing with divorce, be aware that even very young children may struggle emotionally. Short-term sadness and anger are normal. If negative emotions and behaviors continue beyond a few months, experts suggest counseling. Organizations like the Center for Child Counseling can provide expert, age-appropriate therapy to help children during and after a divorce. If an ACE like divorce is not addressed adequately, children may be impacted long-term and have a higher likelihood of using drugs and getting involved in criminal behavior later in life.

Adults Recall the Childhood Trauma of Divorce

When adult children of divorce look back on their childhood experiences, many express that it was the stress and conflict that was created by the divorce and not the splitting of parents itself that was so difficult to overcome. Often, children are used as pawns or become weapons in the fight between the separating partners. Asking children to choose between parents is extremely traumatic and brings feelings of anxiety and guilt that can last a lifetime.

Most times, parents go into self-protective, offensive mode and “lawyer up” which, while advised for many reasons, can create an immediately hostile and adversarial environment into which the children are inevitably dragged. The numerous emotions adults feel during a divorce—grief, anger, disappointment, loss of control, fear, loss of status, antagonism, bitterness, sadness, etc.—may also be experienced by children in different ways and for different reasons.…and if adults find it difficult to identify and cope with the emotions being raised, how much harder must it be for a child’s growing brain to process?

Parents who prioritize their children’s needs during a divorce should be viewed as heroes who have managed to look beyond their own emotions and chosen not to put their children at risk for long-term repercussions associated with ACEs.

Minimizing the Impact of the Process

You don’t have to put your own interests/needs last in order to put their children’s interests first. There are different ways to get a divorce. Parents can try to choose a non-adversarial form of divorce, if possible. They can consider mediation or collaborative resolution, if the nature of the divorce allows for it. It’s cheaper and often less traumatic for everyone involved.

Of course, there are as many different kinds of divorce as there are marriages. Some divorces are divisive and going to court may be inevitable. Center for Child Counseling board member and partner at Ward Damon, Eddie Stephens views ACEs from a family court perspective. He sees the trauma in families going through divorce: “There is an incredible amount of dysfunction out there. It is on full display in family courtrooms across the nation. Most professionals are just dealing with symptoms (substance abuse, violence, reckless behaviors), but little is done to address the root cause. In more cases then not, these individuals have suffered through some kind of traumatic experience(s) as a youth. That is the problem that needs to be addressed… not just the symptoms.”

Stephens sees how childhood trauma is transmitted from one generation to the next.

“The goal should be to create a trauma-informed society that appreciates the impact ACEs can have on an individual throughout their lives. If we shifted resources and provided the needed therapy when these kids were young, we would be more likely to stop the generational cycle which would lead to a healthier society. If we don’t embrace that approach as a society, we will continue to spend money on the symptoms while further generations become entrapped in this horrible cycle of dysfunction.”

Try to Have a ‘Grown-Up Divorce’

Children mimic grown-ups’ behavior. They learn what maturity is by watching adults. Parents teach us lessons of sharing, listening, playing fair, and being honest and kind, yet so often these simple rules are broken during a divorce. For a little brain seeking to process these events, it’s all very confusing. Positive or negative world views are being formed at this stage of life and witnessing a mature versus an acrimonious divorce can skew a child’s views on the safety or danger of adult relationships for the rest of their lives.

Mature parents can minimize the impact of their divorce by focusing on some simple guidelines. They may sound like common sense but, in the heat of the moment, practicing these rules can be a challenge. However, it will benefit your child during your divorce and for the rest of their lives.

Communicate:

Wherever possible, communicate decisions about the divorce as a family. Ideally, if all parties are present, the child will understand what is happening and see that both parents still love them. Do not share intimate details of the causes of the divorce; share age-appropriate facts only. Avoid the “blame game” or “he said, she said” story-telling.

Prepare:

Tell your children ahead of time what will be happening and when. Nobody, especially a child, likes to be sidelined by dramatic, unexpected events. Tell your children, as early as possible, about major life events like moving houses, changing schools, etc.

Acknowledge Emotions:

Don’t try to pretend that this decision is the best choice and “better for everybody”. Your child may not feel that way. Empathize with their sadness and fear and allow them to talk about their emotions. Always allow them to talk positively about the other parent.

Prevent Stress:

Try not to expose your child to adult concerns. Ensure they don’t overhear cruel arguments or intimate issues. You need to walk a fine line between keeping them informed and protecting them from age-inappropriate facts, no matter how true.

Provide Structure:

Some of the biggest changes for a child going through a divorce is the loss of significant time with one parent or the other and the constant moving between new living spaces. If you can agree on universal rules that are obeyed at both homes, it will reduce stress for your child. Try to maintain routines and not change/cancel plans at the last minute. This will only add to your child’s anxiety and insecurity.

Keep Loving Buffers in Their Lives:

Your child should never have to choose one parent over the other and that goes for extended family members, too. Your child may be very close to your ex’s siblings (their aunts, uncles, and cousins) and your ex’s parents (their grandparents). These positive influences in their lives can help buffer against the stress of the divorce and minimize the effects of ACEs. Do your best to nurture those relationships and let your child enjoy the stability of still having these good, kind people in their lives.

Use Kind Words:

In the case of biological children you have in common, it helps to remember that your amazing, precious children are 50% your ex. Every bad thing you say about him or her, you’re saying about the children you share, too.

Don’t Force Them to Hide Things From You:

Your children are likely to feel torn or periodically disloyal during and after the divorce. Allow them to share positive thoughts or feelings about your ex. They shouldn’t feel that they have to hide funny stories or happy thoughts about your ex from you. You can find ways to reinforce these in a way that’s both honest and supportive of their feelings:

“I always loved how smart your mom is.”

“You dad always tells the best jokes.”

Love Them Extra:

It goes without saying that during this difficult time you should support your child even more than usual. Smother them with love and encouragement. In the case of an especially hard divorce, you might try to remind yourself that you love your child more than you hate your ex.

There is no reason your divorce should be a childhood trauma that scars your children for life. So many parents manage to get it right and provide two secure, stable and happy homes for their children after their divorce. The ultimate goal is not to “win your divorce” but for your children to have a lifelong positive relationship with both their parents.