Since the beginning, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and the criminal justice system have been inextricably linked. The original 10-question survey acknowledged this by asking whether a child had a parent who was incarcerated. The effect of this kind of sudden loss on a child can be potentially devastating in the absence of a compensating buffering influence. But adversity and the justice system cross paths in many ways, let’s explore some of them here and discover ways in which we can become better at helping children with ACEs and those adults trying to address their own negative childhood experiences.

In the United States, there is undoubtedly a link between literacy and incarceration. 85 percent of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally low literate. These are likely youngsters who have been struggling at school. Partner with that the fact that juvenile incarceration reduces the probability of high school completion and increases the probability of incarceration later in life and you can see that early negative indicators like poor social skills and self-regulatory difficulties (often identified as early as kindergarten) are reliable in tracking poor future outcomes. It seems depressing to be betting against our children in this way but the correlation between early struggles and ultimate incarceration are so clear that these metrics are, sadly, reliable. It’s our job to intervene and disrupt the pipeline of despair that moves children from childhood adversity to contact with the juvenile justice system to adult incarceration. We need to help children before they fall apart through prevention and intervention services and improved education for those working in the juvenile justice system.

In the United States, there is undoubtedly a link between literacy and incarceration. 85 percent of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally low literate. These are likely youngsters who have been struggling at school. Partner with that the fact that juvenile incarceration reduces the probability of high school completion and increases the probability of incarceration later in life and you can see that early negative indicators like poor social skills and self-regulatory difficulties (often identified as early as kindergarten) are reliable in tracking poor future outcomes. It seems depressing to be betting against our children in this way but the correlation between early struggles and ultimate incarceration are so clear that these metrics are, sadly, reliable. It’s our job to intervene and disrupt the pipeline of despair that moves children from childhood adversity to contact with the juvenile justice system to adult incarceration. We need to help children before they fall apart through prevention and intervention services and improved education for those working in the juvenile justice system.

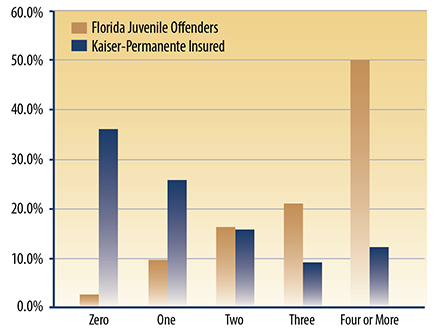

ACEs Among Juvenile Offenders

By the time any child comes into contact with law enforcement and the judicial system, it’s highly likely that they have already experienced trauma and adversity in their lives. 90% of young people in the juvenile justice system have at least one extreme stressor and usually far more. In fact, juvenile offenders in Florida have starkly higher rates of ACEs than the population as a whole, according to a study conducted by the state’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and the University of Florida. The study (“The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) in the Lives of Juvenile Offenders”) surveyed 64,329 juvenile offenders, only 2.8% reported no childhood adversity compared to 34% surveyed in the original CDC study. That means 97% of them had at least one ACE. 50% of the offenders surveyed reported 4 or more ACEs putting them in the high risk category (this compared to just 13% in the original study). This data is incredibly significant because numerous studies link a high ACE score with chronic disease, mental illness, violence, being a victim of violence, and early death. When you raise a child with violence, they have a tendency to become violent. Fortunately, the same is also true when you raise a child with love and kindness.

Who Are These Children?

But let’s consider the children behind the statistics because all of them are children under the age of 18. Children in the juvenile justice system have committed offenses that range from vandalism and delinquency to DUI and drug offenses to more serious crimes like assault, rape, and murder. In the US, the most common crime committed by juveniles is theft. This can include shoplifting, robbery, burglary, and other property theft. There may be a tendency to think of boys as more prone to ‘delinquency’ but the percentage of girls in the juvenile justice system has increased over the decades, accounting for approximately one-third of all arrests.

These young people are obviously making bad choices but the ACEs they suffer from are not one of those bad choices. Their ACEs have been thrust upon them since birth. They have accumulated the trauma, risk factors, and toxic stress associated with high ACE scores. They come from troubled homes where substance abuse is rife, many have suicidal or mentally unstable parents, they are abused or neglected, they’ve witnessed violence at home and in their communities, and many of them have suffered the loss of a parent to death, divorce, or the criminal justice system. Often, their exposure comes from multiple types of interpersonal victimization—polyvictimization—but also from other childhood adversities (such as separation from their biological parents and/or impaired family relationships). In other word, these children have been traumatized from all sides before they ever commit an offense.

Without removing culpability for their crimes, it is important to consider the context in which those crimes were committed and how much blame can be laid at the feet of children for their actions. We’ve already learned that the human brain is not fully developed until the early twenties, making tweens and teens physiologically incapable of fully understanding consequences in the way a mature adult would.

The Current Situation

Each year, the United States locks up more than 130,000 young people under the age of 18 at a total cost of $6 billion, or an average of $88,000 per inmate. Currently, there are 70,000 juveniles living in correctional institutions. A study co-authored by MIT economist Joseph Doyle found that juveniles who were incarcerated for their offenses are 23 percentage points more likely to end up in adult jails later in life compared to those who were sentenced to alternates like counseling, rehabilitation, or community service. Put another way: 40 percent of kids who went into juvenile detention ended up in adult prison by the age of 25. Apparently, non-custodial sentences garner better results and it seems that locking kids up is just a great way to create future adult criminals.

Despite these facts, the juvenile justice system isn’t going away. Given that we know incarcerated kids are traumatized, at the very least, we need to work towards a more trauma-informed juvenile justice system.

What Exactly is a Trauma-Informed Juvenile Justice System?

(Based on SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma-Informed)

A trauma-informed juvenile justice system…

• realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery

• recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system

• responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices

• seeks to actively resist re-traumatizing already-traumatized children

Some juvenile justice systems across the country are committed to this approach. They’re talking about parent and caregiver trauma, and how best to reach and engage families in the process. They’re also developing best practices in cross-system collaboration with child welfare, the education system, and healthcare providers. They’re trying to break down the barriers to ‘continuity of care’ while still respecting established privacy legislation.

Goals for the Juvenile Justice System

Here are a few steps recommended to help make the juvenile justice system better at managing and helping the children in their care who suffer from high ACE scores:

1. Make trauma-informed screening, assessment and care the standard in juvenile justice services.

2. Abandon juvenile justice correctional practices that traumatize children and further reduce their opportunities to become productive

members of society.

3. Provide juvenile justice services appropriate to children’s ethno-cultural background that are based on an assessment of each child’s

individual needs.

4. Provide care and services to address the special circumstances and needs of girls.

5. Provide care and services to address the special circumstances and needs of LGBTQ (lesbian/gay/bisexual/transsexual/questioning) youth.

6. Develop and implement policies in every school system across the country that aim to keep children in school rather than relying on policies

that lead to suspension and expulsion and ultimately drive children into the juvenile justice system.

7. Guarantee that all violence-exposed children accused of a crime have legal representation.

8. Help (rather than punish) victims of child sex trafficking.

9. Whenever possible, prosecute young offenders in the juvenile justice system instead of transferring their cases to adult courts.

Prevention Would Preclude a Lot of Pain

No matter how sophisticated our juvenile justice system becomes, however, it’s clearly still better to prevent children ever getting on the path to incarceration in the first place. Prevention wins every time over the negative implications of incarceration for the individual and the cost, socially and financially, to society as a whole.

Every recent study on juvenile offenders strongly suggests that efforts should be focused on the early identification of ACEs and intervention to improve a youth’s life circumstances. This approach of intercepting the issue upstream will reduce the likelihood of criminal activities and the resulting impacts on the system.

Recent studies suggests:

• Funding primary prevention efforts like educating parents about encouraging a child’s brain development

• Making sure that health professionals are screen for ACEs at periodic intervals during childhood

• Educating school personnel on the signs and symptoms of ACEs, as well as the fact that maladaptive, antisocial behaviors often stem from

them. Suspending or expelling students from school may deprive youth of the safest environment they can access. In-school programs to

address bullying, disruptive behavior and aggression can help youth in safe environments while they learn regulatory skills.

• Ensuring that law enforcement and judicial awareness of ACEs will enhance the likelihood that the root causes of problematic behaviors will be

addressed with social and behavioral health services.

Prevention and early identification of ACEs will improve the general health of communities and reduce costs in medicine, social services, and criminal justice. Nancy Hardt, one of the authors of the Florida-based study says. “Development of educational curricula, health programs, and policies to detect and treat physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse and substance abuse among youth has the potential to reduce their involvement in the criminal justice system.” She also acknowledged that increased primary prevention will require collaborative efforts and effective communication across health, education, and community programs. We concur!

Schools provide a unique opportunity for experts like the therapists from the Center for Child Counseling to make a difference in children’s lives since teachers often see emerging issues long before the before the criminal justice becomes involved. As Hardt declares: “It’s time for justice, law enforcement, healthcare, and schools to all get together on behalf of these children who are experiencing ACEs.”

Together, we can build our children’s defenses, despite their ACEs, to make good choices and avoid going down the wrong path to incarceration and all its associated sadness, lost opportunity, wasted potential, and pain. You can help support our unique prevention and early intervention model in schools by donating directly to our School-Based Mental Health Program here.

Sign up now for news, events, and education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and promoting resilience.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from: Center for Child Counseling, 8895 N. Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, 33410. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email.